sys·tem·ic/səˈstemik/

adjective

- relating to or involving a whole system

Systemic Racism includes the policies and practices entrenched in established institutions, which result in the exclusion or promotion of designated groups. It differs from overt discrimination in that no individual intent is necessary.

In this section, we’ll examine how racism is embedded in the justice system, education, health care, foster care, artificial intelligence, and even issues pertaining to the environment.

Systemic racism is such a huge concept, it’s hard to understand its effects. In the clip below, Sheridan College professor Michaelann George breaks down systemic racism to its roots and describes the impact it has on every individual.

Systemic racism can be seen in things like how much money you make. A recent report from Statistics Canada found women only earned $0.87 for every dollar men earned, but Indigenous women were the most affected. They earned 36% less than non-Indigenous men. Racialized women earned 34% less than white men.

For First Nations people, systemic racism is a force of oppression embedded within government structures. As noted by Jesse Wente, an Ojibwe broadcaster, curator, producer, activist, and public speaker,

“The whole point of a colonial government is to take from Indigenous people.”

Therefore, it is very difficult for Indigenous people to work within existing government frameworks. Wente expands on that concept in the clip below.

Racism in the Justice System

One of the areas systemic racism is most prevalent is the justice system, including carding in Toronto, Halifax street checks, and policing in places like Timmins and Winnipeg.

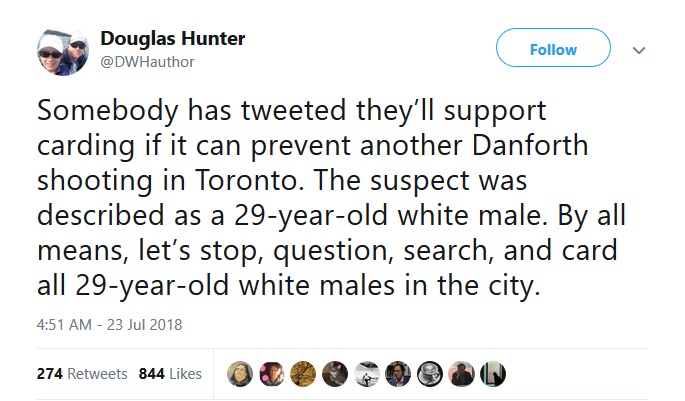

Toronto Carding

Carding is officially called the Community Contacts Policy. It is an intelligence gathering effort of the Toronto Police Service where people are stopped and questioned. The interactions are documented even when no offense is being committed.

However, an independent review of street checks proved they don’t work. The report was done by Court of Appeal Justice Michael Tulloch who was asked to perform the review in 2017 by the Liberal government.

The random, unfocused collection of identifying information outweighs the social cost of the practice of carding. The amount of time used to practice carding is valuable time that could be used for other objectives.

There is little evidence to show the practice is useful in reducing crime, but much evidence that it disproportionately affects racialized individuals. A journalist from Toronto wrote an award winning story for Toronto Life called, The skin I’m in, where he talks about how he has been stopped and interrogated by police more than 50 times.

Carding was actually made illegal in 2013 and violates the Charter and Human Rights Code, but only the recording of the information. Police stopped using physical cards but can now use something called a street check or can write the interaction down in their memo book as Community Safety Notes which can be stored for a maximum of seven years.

Under the new legislation, police must explain to people they stop that they don’t have to talk with them and that their refusal to talk cannot be used against them to compel them to give information. Police also must explain their reason for stopping them and provide a receipt of the interaction, including the officer’s name and badge number and information on how to contact the Office of the Independent Police Review Director.

Halifax Street Checks

2017 the Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission ordered a report to be completed after a United Nations group raised concerns about systemic discrimination and racial profiling in police street checks in Nova Scotia. Scot Wortley, a University of Toronto criminology professor, authored the report and said,

“Street checks have contributed to the criminalization of Black youth, eroded trust in law enforcement and undermined the perceived legitimacy of the entire criminal justice system.”

The 180-page report found street checks in Halifax were second highest in Canada, behind only Toronto.

The report says that between the years of 2006 to 2017 the Halifax Regional Police and the RCMP stationed there had stopped Black men for a street check 9.2 times more than white men in Halifax, Black women were also found to be stopped three times more.

While African Nova Scotians make up only 3.6% of the population they were involved in 19.2% of all street checks. Wortley also stated that these statistics only include data for street checks and are just the “tip of the iceberg.”

Community consultation and surveys were conducted to gain a better grasp of how people viewed the police, many Black Nova Scotians talked about how they had been disrespected by police in the past and shared stories of being questioned, harassed, bullied and, assaulted.

Officers even admitted that they knew the street checks were of questionable quality but performed them in an effort to get their arrest numbers up. Halifax Regional police chief Jean-Michel Blais said he would look at the review in detail to help him make initial and long term changes.

Policing in Timmins

After a five day trip to Timmins, Ontario, Renu Mandhane, the chief commissioner of Ontario human rights, said that racism towards Indigenous people had been normalized on the police force:

“We did get the sense that there is a pervasive level of racism that Indigenous people experience in Timmins.”

Mandhane also criticized the treatment of Indigenous people at the institutional level in Timmins. She said the police aren’t speaking constructively with First Nations representatives:

“To varying degrees, there just seemed to be a lack of awareness of the need to prioritize service delivery to First Nations people in a culturally competent way.”

Jennifer Wabano, who sits on the Indigenous Advisory Committee in Timmins says she worries about whether or not police in the city will keep her children safe. Even after years of efforts have been made to bring the community together, the distrust of the police is still alive and well.

Timmins’s mayor acknowledged the need for introspection but pushed back at the notion that the city is racist.

Nishnawbe Aski Nation Grand Chief Alvin Fiddler, Mushkegowuk Council Grand Chief Jonathan Solomon and Fort Albany First Nation Chief Andrew Solomon wrote,

“We have seen systemic racism in the city of Thunder Bay, and must now wonder if this is also happening in Timmins.”

The quote above refers to a report from Thunder Bay that identified its Police Service’s sudden death investigation was so problematic that at least nine investigations needed to be reopened.

The Thunder Bay force has had an Aboriginal Liaison Unit for more than 20 years. It consists of two officers, which many Indigenous people see as insufficient. The unit is sometimes described as tokenism.

Tina Fontaine and Winnipeg’s Police Force

Tina Fontaine was 15-years-old when she died in 2014. Her case was one of many missing and murdered Indigenous women. Many First Nations’ people believe her death could have been prevented, and that the Winnipeg Police failed her.

According to police reports, Tina was last seen on the streets of downtown Winnepeg on Aug. 8, 2014 in a youth centre, and again in a truck with a drunk driver, who was not taken into custody. Her body was pulled from the Red River nine days later. In the days in between, she had two encounters with police, and nothing was done despite her missing status.

But her death sparked a change in Canada.

The Canadian Human Rights Commission requested an inquiry into the number of missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, newly elected, appointed five independent commissioners to consult with families, activists, and others to structure the inquiry.

A volunteer group called Drag the Red was also created. The group routinely drags the Red River in Winnipeg to find bodies or evidence. The Strong Hearted Buffalo Women Crisis Stabilization Unit was also formed, a crisis intervention program created to help Indigenous girls at risk of sexual exploitation.

In the graphic below we’ll tell you about the difference in the way Indigenous people are treated in the justice system as opposed to non-Indigenous people. Below the graphic we’ll tell you about the trauma people experience as a result of systemic oppression.

nîpawistamâsowin: We Will Stand Up, is a documentary by Tasha Hubbard that opened at Toronto’s Hot Docs Festival. According to The Star, the documentary tells a story through the perspective of Indigenous people and tells their truth. The documentary sheds light on the story of Colten Boushie. A 22-year-old man who was shot in the head by Gerald Stanley, a Saskatchewan farmer. Stanley was found not guilty of second degree murder. Boushie’s cousin, Jade Tootoosis, called on the United Nations Permanent Forum to investigate the racial biases against Indigenous people in the Canadian judicial system.

The Trauma of Racism

There is new research on race-based trauma. People become traumatized from experiences of racism or oppression due to their ethnic or racial identity and ongoing experiences of blatant and subtle racism, or micro-aggressions. Symptoms include always looking for danger, feeling anxious, isolated, and not wanting to interact with other people. Dr. Monnica Williams thinks every Black person has experienced some form of racial trauma that can result in PTSD. She has developed a new treatment for people of colour to deal with ongoing trauma. When challenged on her definition of PTSD Williams responded,

“Let me break it down for you. Imagine you were minding your own business, and a person with a gun pulled you over, forced you to get out of your car, pulled everything out of your car, threw it on the ground, said they were looking for something you knew you didn’t have, stripped off all your clothes, and cavity searched you in public and then drove away, would that not be traumatic to you? We don’t think twice about it because we’d like to believe that is a part of our justice system, but it’s not.”

Many people think that we’ve come far from officers that misuse their power, but that’s not the case. The video below was taken on March 21, 2019 when Dyma Loving was arrested for expressing her concern after having a gun held to her face. She was taken in for disorderly conduct by the Miami-Dade police, although the video below tells a different story. Her charges were dropped and the officer was suspended for his actions.

WARNING: This video is quite disturbing.

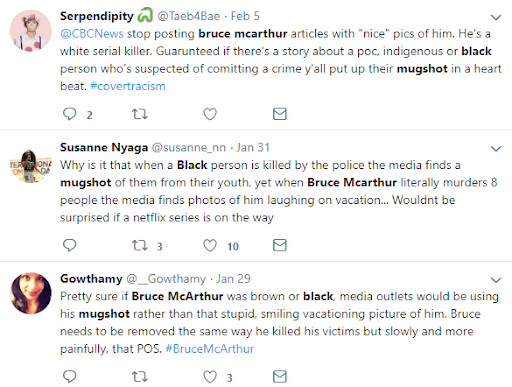

The Mug Shot Controversy

There was a lot of controversy over the mug shot of white serial killer Bruce McArthur not being released. People on social media were infuriated by stories showing pictures of McArthur smiling, while suspects from other races were identified using mugshots. When CityNews addressed the concerns to Toronto Police they said,

“When we first announced the arrest of McArthur, we did not want to release his photo in an effort to ensure the integrity of any information that came forwarded. This was explained during the news conference. At this stage, there is no investigative reason for us to release his photograph. If that should change, we would certainly reconsider.”

Acknowledging these cases are not directly comparable and involve a different police force, we did find these examples in the Greater Toronto Area of mugshots being used after a suspect was arrested. In these instances, both suspects are racialized: one was arrested for second-degree murder after turning himself in, but police still released his mug shot. Similarly, the other was arrested for attempted murder and his mugshot was also released to media.

Education

Racism, unfortunately, is still present in our modern education system. Peer bullying often still ends in racist physical and emotional abuse. There are also underlying issues that lead to widespread conflict. One of the most prominent examples is the Cole Harbour High School brawls that happened 30 years ago. A major fight broke out between 10th graders during a snowball fight, with those involved falling into sides based on race. Older friends and family members of the 10th graders traveled to the school once they caught wind of what was happening, creating more havoc. This resulted in two days of violence. One report found socioeconomics also played a role in the Cole Harbour brawl. The event led to the creation of the Black Learners Advocacy Committee, or “BLAC,” and a five-year study examining issues of racism.

The BLAC report defined racism not just as a battle between races, but a power imbalance:

“…all races discriminate and all races may have some prejudice but not all races possess the power to carry out racist acts to the same extent. Racism includes the power to oppress a subordinate group—”

The committee made recommendations for a proposed organization that would span across all of Canada and have influence over things like how school systems portrayed Black people culturally and throughout history. That organization was never created. A follow-up report found some other strategies suggested in the report were implemented successfully, but there were still issues:

“…transformation on a large scale does not necessarily translate into change on a daily level or touch the lives of those it is intended to serve.”

In the graphic below, we’ll show you how Black students are treated differently from white students when punished in school. Below the graphic, we’ll take a deeper look at how racism can even pop up in curriculum.

A study on racism in Canadian curriculum found race is a social construct, but has real-world consequences. Discrimination can either be based on race, or ethnicity. It is not a matter of misunderstandings between groups, but a matter of having political power, and is based in the belief that inherent differences between people make one superior or inferior to another. While Canada had one of the first multicultural policies in the world, and school curriculum has been heavily edited to remove racist and sexist works, racism is still “embedded in the school consciousness.”

Ratna Ghosh says the “hidden curriculum” refers to how students are socialized at a young age and how the individual ideologies of teachers impact students. Ghosh suggests teachers must examine their own values because they directly shape the lives of so many people. Ghosh also advocates implementing “the three C’s”: concern, connection, and care. This means teaching students to be concerned enough to want to evoke change, to connect to others to build trust within a collective society, and to instil a caring attitude that helps eliminate boundaries that the hidden curriculum creates.

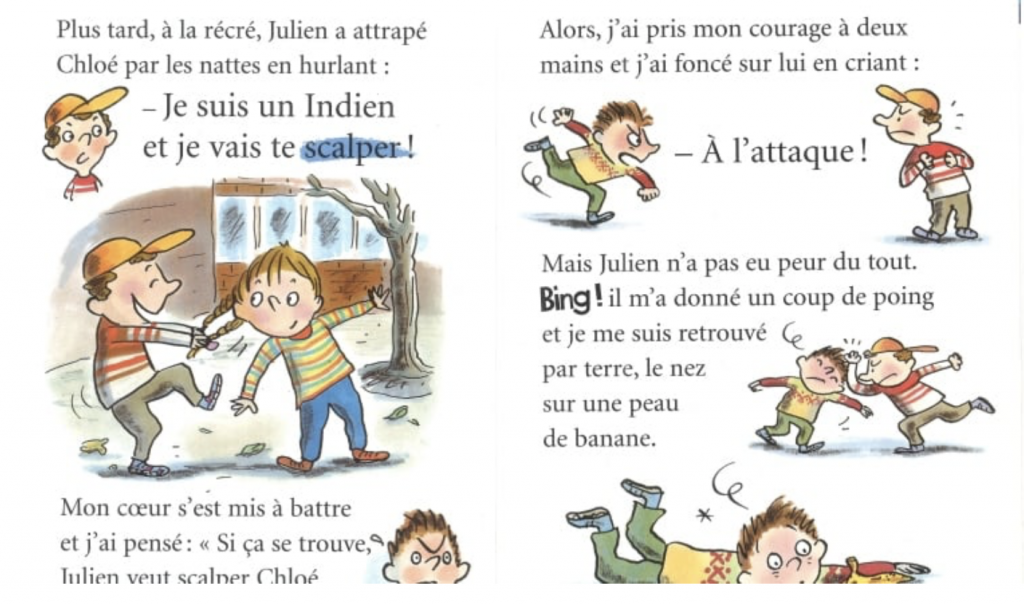

Other forms of racism can be seen in what is taught in textbooks.

A fifth grader in Quebec went to her mother after finding a picture in a french textbook that showed an illustration of one child holding another’s hair accompanied by the phrase, “I am an Indian and I will scalp you!”. Quebec’s education minister, Dominic Cardy, and the girl’s school principal have both reached out and apologized. But it raises the questions, how did this illustration make it into the classroom in the first place and how many more books in schools across Canada contain similar forms of racism?

Acknowledging and understanding what was taken away from Indigenous people is a start but there is so much more that can be done on an individual level, even by students. You don’t need power and authority to make a change. Hayden King, Gchi’mnissing Anishinaabe educator/writer and the director of the Centre of Indigenous Governance at Ryerson University, says students either forget or don’t understand how much power they have. King expands on what they can do in the clip below.

According to a journal, racism in Canadian history is not as upfront as it should be in textbooks. A limited amount of racial discrimination is highlighted in Canadian history texts. It’s talked about and discussed extensively for the Second World War era, but is treated as a “then and there” problem, not as a “here and now” problem. Canada’s issues with racism are also downplayed when comparing the history of discrimination between America, Canada, and the U.K. Canada is often portrayed as an inclusive and diverse nation compared to others.

Factors such as a lack of funding, less advanced learning opportunities, being denied to wear accessories from their culture, and harsher punishments based on race also count as forms of racism and/or discrimination against certain groups of students.

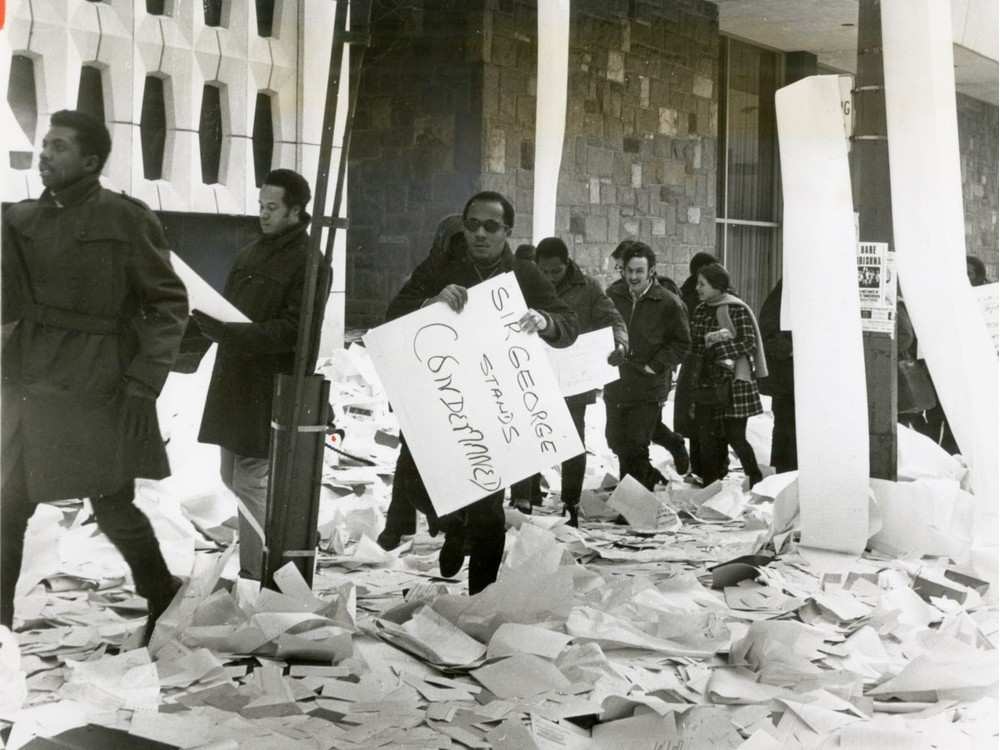

Sir George Williams Protest

In February of 1969, hundreds of students at Montreal’s Sir George Williams University (now Concordia University), barricaded themselves in the school’s computer room to protest against a professor, Perry Anderson, who was accused of discrimination. The protest led to the “Sir George Williams” riot, where 97 people were arrested and over $2 million of school property was destroyed. It has been called the most important student protest in Canada in the 1960s.

Most of the students were given amnesty and allowed to return to school. The leaders, however, Anne Cools and Rosie Douglas, were arrested. (Douglas was deported, but became the Prime Minister of the Caribbean island of Dominica. Cools helped found one of Canada’s first women’s shelters.) After the protest, the university revamped some key policies, adopted regulations on the university’s rights and regulations, and established an ombudsman’s office (an official who represents the public interest in case of rights violations).

Black Montrealers rallied with the students, and the community organized a summer school to help Black students prepare for postsecondary education. A school that still exists to this day. In January of 2019, a play called Blackout, developed by a theatre troupe made of young activists known as Table D’Hôte, was performed on the same dates the protest took place, in the same hall where the occupation occurred.

Environmental Racism

Environmental racism is the placement of people into environmentally hazardous areas or environmental hazards being put into areas with high numbers of minority people. It’s a hard concept to understand without knowing who is impacted. Michaelann George, breaks it down in the clip below.

Grassy Narrows

The Canadian Medical Association Journal Group says that mercury poisoning has been an issue in Indigenous communities for six decades. When mercury enters aquatic systems and larger fish eat them, mercury reaches toxic levels. Humans eating mercury-laden fish can cause nervous system damage.

Between 1962 and 1970, the Dryden, Ont. Chemical Company’s pulp and paper mill created mercury waste from bleaching paper. In 1970, George Kerr, who was the Ontario Minister of Energy and Natural Resource Management at the time, told the company to put an end to mercury dumpings. However, 40 years later, the mercury problem still exists on Grassy Narrows First Nation.

Settlements between the Dryden Chemical Company and Ojibwe people have not worked out. Minamata Disease, or in other words, mercury poisoning, is not even an official diagnosis in Ontario despite experts noticing similar symptoms with people in areas affected by mercury-poisoned water. Indigenous people are still fighting for action.

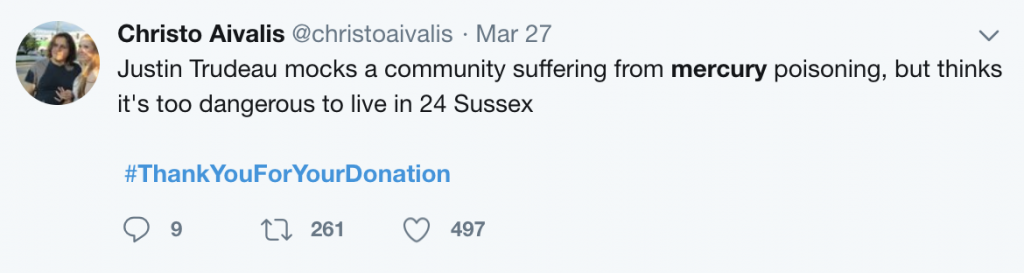

On Wednesday, March 27, 2019, Indigenous protestors confronted Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in Toronto about the mercury poisoning issue in the Indigenous communities of Grassy Narrows and Wabaseemoong, Ont.

Trudeau’s response was “Thank you very much for your donation tonight. I really appreciate the donation to the Liberal Party of Canada.”

The protesters were furious. A #Thankyouforyourdonation hashtag quickly spread on social media. By the next morning, Trudeau was at a press stop in Halifax expressing regret for his sarcastic response.

After saying he was usually respectful and engaging with protesters he said,

“I didn’t do that last night. Last night I lacked respect towards them.”

Trudeau also said he would continue to work with Indigenous Services Minister Seamous O’Reagan to support progress on the issue of mercury poisoning in Grassy Narrows.

Oilsands

Some people believe the impact of oilsands production negatively impacts First Nations communities disproportionately. A 2014 report by two University of Manitoba scientists and Alberta First Nations says that a link exists between oilsands pollutants and high levels of wildlife heavy metals, as well as high cancer rates in people. The study says that there were 23 cases of cancer in 94 study participants. Last December, the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nations tried to block an oilsands expansion project–another challenge for First Nations is resource exploitation.

Water

As noted by George in the clip above, another prevalent issue tied to environmental racism is water quality. We all know that water is an extremely important part of our lives. It is one of the basic things people need for survival. However, even in Canada, the country with the most freshwater in the world, there are issues with water quality for many communities–and this is a rampant problem on Indigenous lands.

Two years ago, Canada had 150 drinking advisories in First Nations areas. Seventy-one of these advisories were long-term, meaning they took place for over a year.

The graphic below will display the long-term drinking water advisories in Canada that have been lifted and the ones that are still in effect. Below the graphic we’ll go into more detail about drinking water and later on we’ll talk about healthcare.

Risk factors of drinking contaminated water include diarrhea, nausea, stomach pains, skin infections, pneumonia, whooping cough, influenza, and even cancer.

Only nine per cent of the Indigenous population in Canada has access to clean water. Many don’t have water pipes that function. This means they have to buy water.

Recently, the Government of Canada decided to work with First Nations communities to improve water infrastructure, end long-term drinking water advisories on public systems, and stop short-term water advisories from worsening. The goal is to have all of the long-term drinking advisories lifted by March of 2021.

Another example of environmental racism concerns the village of Africville in Nova Scotia. It was a close community where many descendants of African slaves lived. Once Halifax’s industrial boom needed dumping sites for waste because of the city’s rapid development, they were placed around Africville, along with an infectious disease hospital. The village was demolished decades later and residents forced to leave.

However, the province is taking measures to prevent environmental racism. In Spring 2015, Nova Scotia passed Bill 111, an Act to address environmental racism. The goal of this Act is to have meetings on environmental racism and how to prevent it in the future.

The problem of environmental racism is also an issue south of Canada’s border, clearly evident in places like Flint, Michigan.

In September 2015, Virginia Tech conducted a water quality study and indicated that 40 per cent of homes had excessive lead levels, not meeting the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) lead and copper rule. Flint is a predominantly Black city. And, years later, the issue still isn’t resolved.

Chester is a small community in Pennsylvania. The population there is 34,000 people and is 70 per cent Black. According to Dr. Marilyn Howarth, a University of Pennsylvania public health expert, there are higher than normal rates of heart disease, stroke, asthma, and cancer in Chester. Poor air has a correlation to this. Cancer, particularly ovarian cancer, has high links to industrial pollution. Howarth says that while connecting cancer, heart disease, and asthma to particular factors may be hard, Covanta plant emissions have carcinogens which increase cancer risks.

According to The Michigan Daily, environmental racism has targeted Black people since the end of slavery. Examples include unfair housing, uneven zoning policies and Black people not being able to speak out on land allocation and use. These factors together have created environmental racism that has led to many health risks involving air and water quality. As a result, there are calls for more diversity in the architecture industry, including the designers and planners at the heart of development.

However, U.S. President Trump is attempting to get rid The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) that protects local communities from environmental threats. NEPA has been an effective tool to battle environmental racism as it helps ensure that communities with predominantly diverse races, that often are vulnerable to pollution, can speak out about decisions that may affect their health.

Health Care

According to a study by Toronto Public Health, racialized people are more likely to have poorer health outcomes than those in

non-racialized groups. In the graphic below we’ll show you what racialized groups face that hinder their status and healthcare accessibility. Below the graphic we’ll talk about Brian Sinclair’s story.

Source: https://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2013/hl/bgrd/backgroundfile-62904.pdf

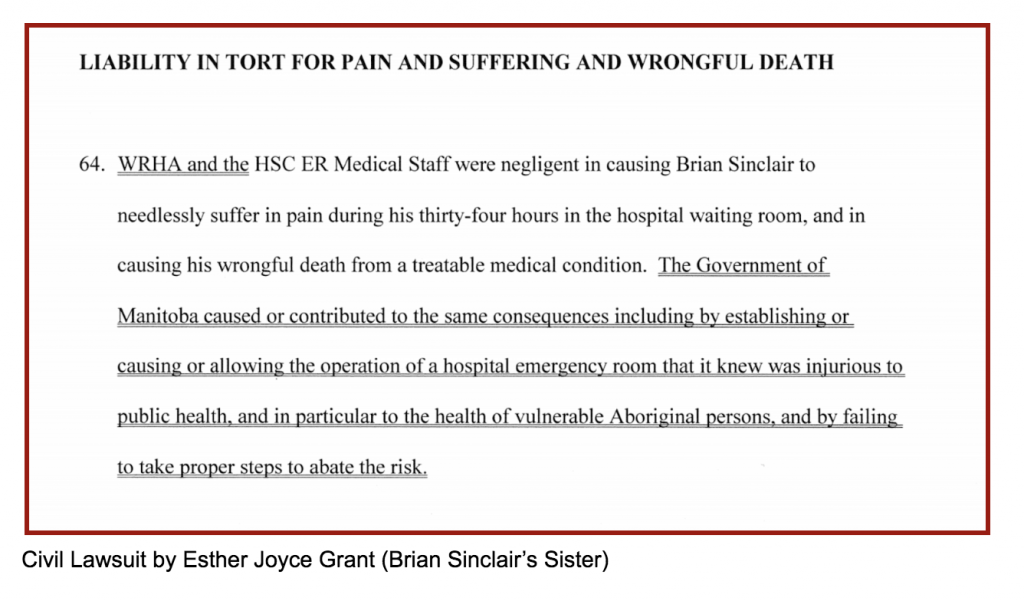

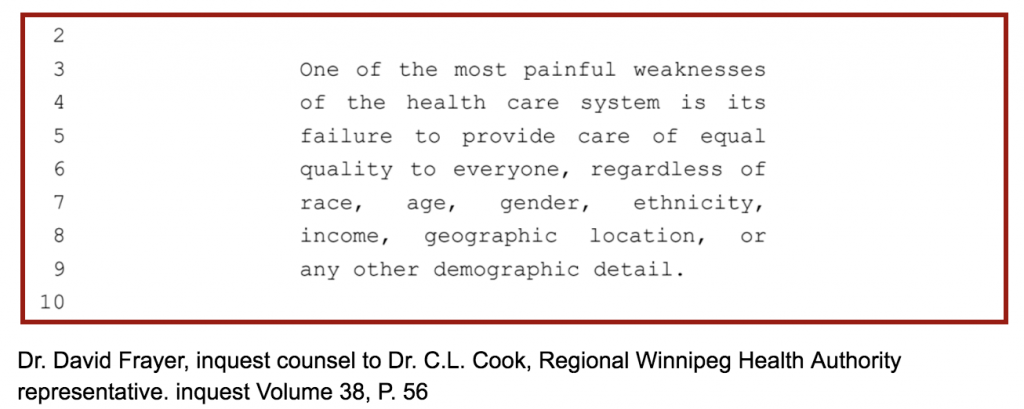

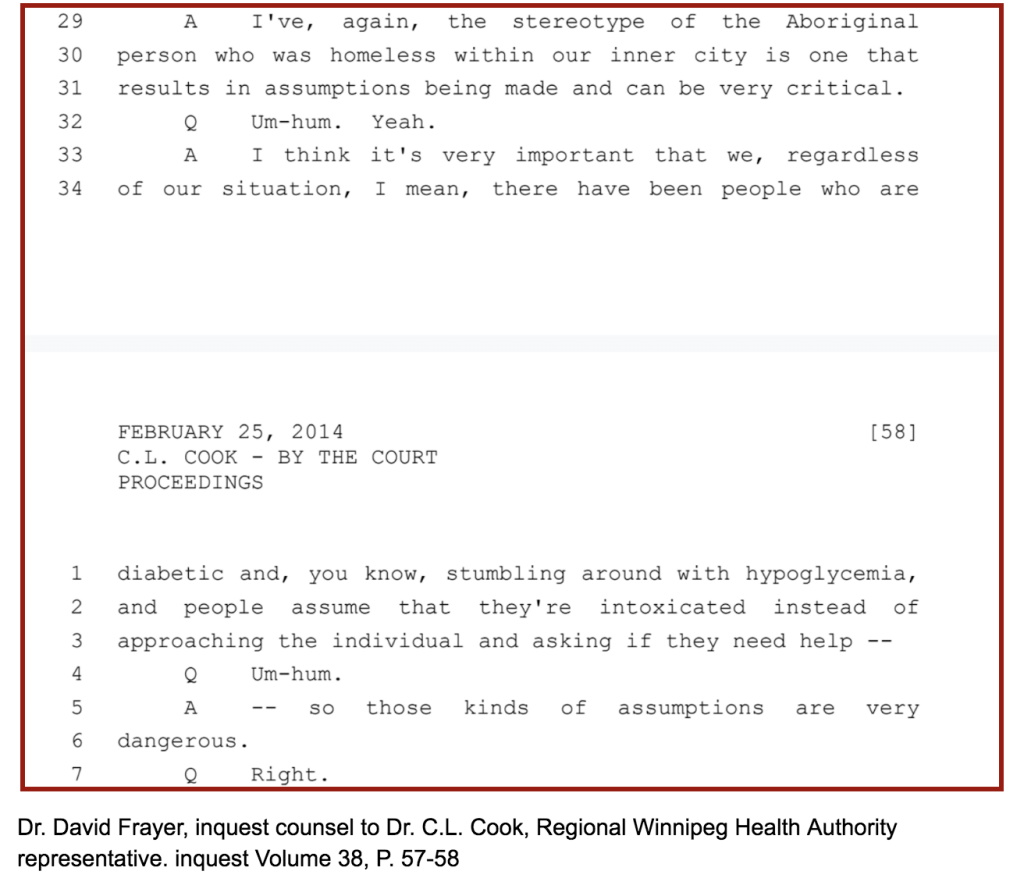

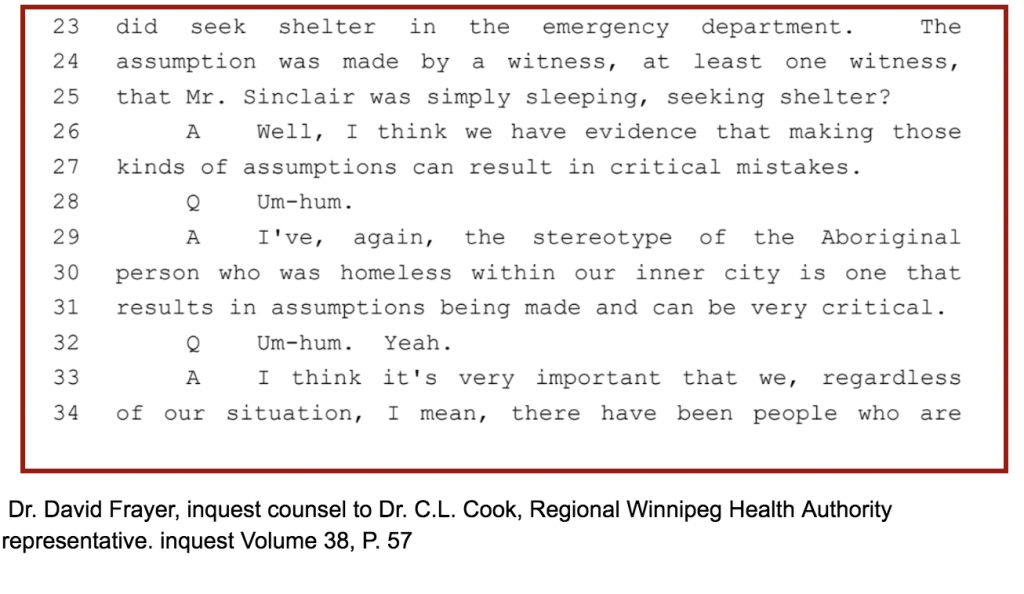

Indigenous people frequently face discrimination within the Canadian healthcare system. The case of Brian Sinclair is just one example. On September 19, 2008, Sinclair, an Indigenous, cognitively impaired amputee, entered the Health Sciences Center of Winnipeg. Sinclair waited patiently for 34 hours to be seen by anyone. He died waiting.

The reason for Sinclair’s visit was due to problems with his catheter. After initial contact with hospital staff, he was ignored despite other patients asking that he be assisted after clear discomfort and vomiting. Sinclair’s condition, acute peritonitis due to severe acute cystitis which was due to a neurogenic bladder, was treatable for hours leading up to his death. In 2014 an inquest was held. It was discovered that assumptions were in fact made about Sinclair based on his appearance including race and disability that likely impacted his treatment. Below are excerpts from the inquest.

In the end, the judge cut the inquest short before making any concrete decisions. No charges have ever been laid. Clayton Ruby, a Canadian lawyer and activist, believed criminal charges could have been laid:

“The HSC and its medical staff had a legal duty to care for and provide medical treatment to Mr. Sinclair. It appears that they knew Mr. Sinclair was in urgent need of care but endangered his life and safety by failing to act even after several non-medical staff and patients alerted nurses to his serious distress. On the basis of the publicly available information (including press reports and the documents released to the Sinclair family by the office of the Chief Medical Examiner) it would appear that the HSC and its medical personnel departed in a marked and substantial manner from the standard of care required of a hospital emergency room and its staff, and that this failure resulted in Mr. Sinclair’s death. Accordingly, there appear to be grounds to lay a charge of causing death by criminal negligence under s.220 of the Criminal Code. This is a serious criminal offence punishable by up to life imprisonment. Moreover, the HSC and its staff had a specific legal duty to provide the necessaries of life, including medical attention for a bladder infection and blocked catheter, food, and water or hydration, to Brian Sinclair, who was a person under their charge. They appear to have entirely failed to do so for 34 hours, and this foreseeably endangered Brian Sinclair’s life. Accordingly, there appear to be grounds to lay a charge of failing to provide the necessaries of life under s.215 of the Criminal Code, an offence punishable by up to five years in prison.”

FOSTER CARE

Maclean’s found shocking percentages of Indigenous children are in foster care, especially in Western and Northern Canada, as represented in the graphic below.

The Government of Canada has co-developed new legislation to limit the number of Indigenous children and youth in foster care. In an effort to improve child and family services for Indigenous people, the Canadian government passed Bill C-92. Prior to this, the Government of Canada came up with six ideas to improve this foster-care crisis:

- • Implement orders of Canadian Human Rights Tribunal, and reform child and family services

- • Shift programming focus to early intervention and prevention

- • Help communities to exercise jurisdiction and look over co-developed federal child and family services legislation

- • Accelerate Indigenous technical tables

- • Support Inuit and Metis leadership

- • Make a data and reporting strategy with provinces, territories and Indigenous partners

Indigenous kids apprehended due to poverty

In a CBC article former child protection worker with the Ministry of child and family development said that a lot of Indigenous children are being taken away as a result of poverty. Factors that may contribute to people placing Indigenous children in foster care are substandard housing and dirty drinking water. Once in care, their parents aren’t easily able to see them and they face many legal issues.

Hi-tech Racism

An ongoing and prominent complaint about A.I. algorithms is the inability of software to identify people of different races correctly. This comes from a lack of training done by the developers–algorithms have less “practice” analyzing the faces of differently raced people and even people of different age groups such as children or the elderly. One of the most eye-opening incidents was in 2015 when a Google photos app mislabelled an African-American couple as “gorillas” in its automatic picture sorting.

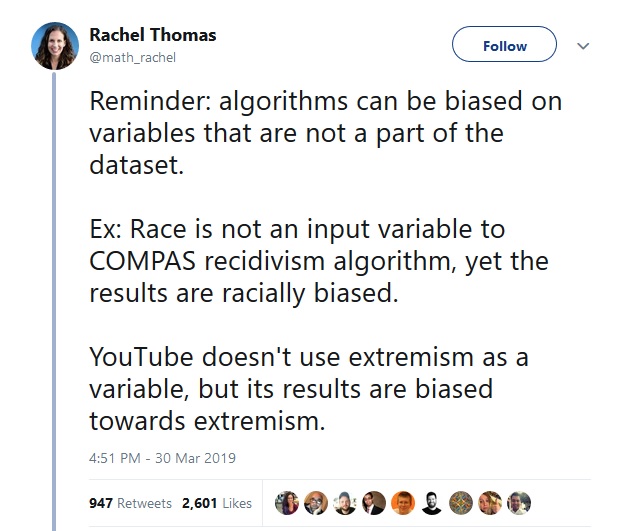

Following the development of facial recognition A.I., several prominent figures have spoken about the issue. Very recently, U.S. Democratic congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez talked about how Algorithms will always be inherently racist as long as there is racism in society, which is the human bias, and if it isn’t fixed algorithms will just be automating the biases.

Another individual who has called for action and change is Joy Buolamwini, a computer scientist who experienced algorithmic racism when she was an MIT graduate when a facial recognition program failed to identify her until she wore an all white mask.

She has since gone on to make the Algorithmic Justice League, which is a website/organization dedicated to helping improve facial recognition technology by highlighting the biases, giving people a safe space to talk about the bias they’ve experienced, allowing people to test out their software for biases, and giving people opportunities to volunteer for facial recognition so that the programs see more diverse faces, thereby making algorithms more inclusive and less biased.

Human bias can negatively affect how an A.I. calculates data, due to direct human interaction and even collected data that it pulls for solutions. This can lead to racist and sexist results on the program’s end. (Epilepsy warning on the video). One of the most infamous examples being Microsoft’s Tay bot, that was purposefully misused by Twitter users as a prank to the point where its generated responses became unbelievably racist and sexist, and Microsoft pulled it from the public. Many large software companies acknowledge this issue, and are attempting to create tools that will identify human bias early enough in development that issues are eliminated.

Self-driving cars

The colour of your skin can also impact how likely you might be to get hit by a self-driving car. Using the Fitzpatrick skin tones range, researchers studied why object detection systems have a hard time classifying people with certain skin tones as pedestrians.

The Fitzpatrick scale is actually based on how easily someone’s skin tone might burn when exposed to UV rays, with 1-3 being lighter tones, and 4-6 being darker. The training set used for algorithms of self-driving systems has 3.5 times more examples of pedestrians with lighter skin than the other end of the skin tone spectrum. So people with darker skin tones, according to the Fitzpatrick scale, aren’t seen as easily by self-driving cars.

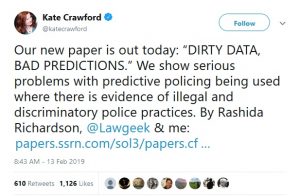

Racist Police Data

More and more police forces are using algorithmic practices to predict criminal activity; however, the data used for these practices can be flawed with systemic and human bias that leads to skewed and possibly incorrect crime predictions. A U.S. report found that practices used to predict crimes were using data corrupted by policing practices, including misinformation caused by racial disparities in arrest rates. Because of this, the data was “dirty” and skewed. In short, the report found that unlawful and illegal policing practices lead to false data which then leads to harmful and inaccurate predictions, creating a feedback loop of confirmation bias related to race, or, in other words, the idea that people of colour are more likely to commit crimes.

In the next section, we’ll examine the difference between cultural appropriation and appreciation.