rac·ism/ˈrāˌsizəm/

noun

- prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism directed against someone of a different race based on the belief that one’s own race is superior.

In this section we’ll examine the psychology behind racism, how it evolves, and talk about some flashpoints of racism, including the wearing of hijabs and use of the N-word.

Racism is an uncomfortable truth. You might think it’s something of the past, but an incident at a 2018 Canadian hockey game proves different. Racist hockey fans hurled insults at Jonathan Diaby, a 24-year-old player on the Jonquiere Marquis. During the game, fans poured beer on his girlfriend and hit his father. Diaby decided to leave the game with his family and they were harassed on their way out. Diaby and his family did not have security or police to escort them out of the building. Players have worries that young aspiring hockey players might see these acts of racism and be discouraged from trying to pursue a career in this field because of their race.

The graphic below details how hate crimes are on the rise in Canada. After the graphic, we’ll explore the psychology of racism, including how it starts in childhood.

Racism is something that many people ignore without even realizing it. A bias that is created through societal views and a lens that differs from person to person.

Studies done by the Social Cognition Laboratory at York University show that, when tested by eye movements, white subjects were less likely to look into the eyes of black faces, unlike when they looked at their white counterparts. Instead, they focused on the lips and nose of the black faces.

This kind of racism is what psychologists call “aversive racism.” It’s not blatant views of hate and discrimination against people of colour–aversive racism is a subtler expression of hesitation towards members of a minority group, and people may not even be conscious of doing it.

But where does it start?

Children and Racism

Research conducted by Professor Jennifer Steele at York University found racial preferences exhibited from an early age. A study of 359 white children revealed that those aged five to twelve showed a greater automatic positivity of association towards white children who looked like them, as opposed to Black children.

But older children who were exposed to a more diverse selection of people through school showed a neutral reaction towards both Black and white children. When asked to categorize images of white children versus Black children into pleasant and unpleasant categories, the decision was made primarily on expression, not skin

“Children have some awareness of race from an early age. So, research suggested that taking a colour-blind approach – or pretending race doesn’t exist – isn’t the best approach.”

So if children become familiar with a more diverse range of people, could it solve the issues of racism? Unfortunately, this is not the case. Things change as we age.

Michaelann George is a social service worker and program coordinator for the community worker outreach and development programs. She’s been a full-time professor at Sheridan since 2010. Michaelann is part of a team that provides non-violent crisis intervention training to social work students. She is passionate about social justice and works diligently to help raise awareness about injustices occurring both within Canada and internationally–and has experienced racism first-hand.

In the video below Michaelann shares a personal experience of how she and her daughter faced discrimination, after bringing Halloween treats to her daughter’s classroom. After the video, we’ll explore the psychological reasons behind racism.

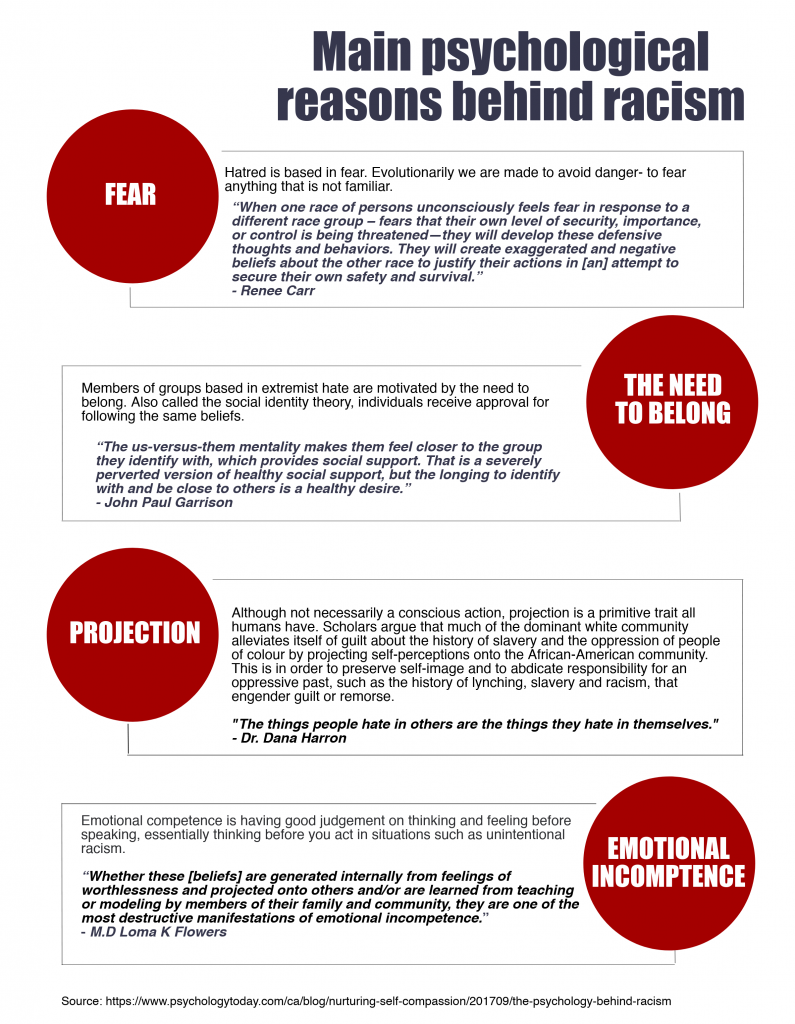

Social psychologist Allison Abrams believes that there are consistent factors that help explain the biases that form when it comes to racism, detailed in the graphic below. After the graphic we’ll talk about racism faced by Canada’s First Nations peoples, and the Truth and Reconciliation Report.

Truth and Reconciliation

Racism and oppression have devastated Canada’s First Nations communities, and residential schools are at the root of many current issues. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada was part of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement. This commission travelled across Canada to hear the stories of more than 6,000 Aboriginal Canadians who were taken from their homes as children. Residential schools were

“…created for the purpose of separating Aboriginal children from their families, in order to minimize and weaken family ties and cultural linkages, and to indoctrinate children into a new culture—the culture of the legally dominant Euro-Christian Canadian society.”

The main goal of the final report was to inform Canadians about the complex and overlooked history of residential schools and to provide a map of how to move forward. It included over 92 calls to action, some to change laws to create a justice system that would be fair to Aboriginal citizens because when the original laws were written, they were written to try and erase Aboriginal culture from Canadian society. Throughout this project, we’ll explore how First Nations peoples are still impacted by racism.

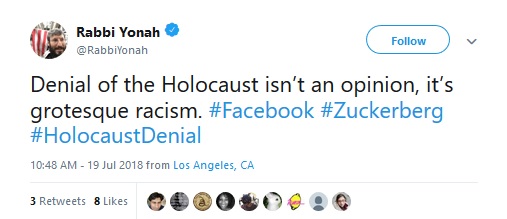

Holocaust Deniers

Holocaust deniers are antisemitic and believe that the Holocaust was exaggerated by the Jews, or that it simply never happened.

“These views perpetuate long-standing antisemitic stereotypes, hateful charges that were instrumental in laying the groundwork for the Holocaust. Holocaust denial, distortion, and misuse all undermine the understanding of history.” (USHMM)

Historian Deborah Lipstadt says, “Denial of the Holocaust is antisemitism and prejudice parading as rational discourse.” Hear more of what she has to say in her TedTalk below.

The United States Memorial Museum defines Holocaust denial as,

“an attempt to negate the established facts of the Nazi genocide of European Jewry. Holocaust denial and distortion are forms of antisemitism. They are generally motivated by hatred of Jews and build on the claim that the Holocaust was invented or exaggerated by Jews as part of a plot to advance Jewish interests.”

Social media are where we share our emotions and opinions with the world. A study by ADL (Anti-Defamation League) showed within in a one year span from January 2017 to January 2018, 4.2 million antisemitic tweets were posted. ADL says that that number is

“large enough to underscore the powerful harassment that exists and the ease with which a relative handful of users can infect our shared social media environment with negative stereotypes and conspiracy theories about Jews.” (ADL, 2018)

But, how much should we be allowed to say? Should people be allowed to voice their hate and racism all over social media for people to see? We’ll explore these ideas more in the Moving Forward section.

Islamophobia

Islamophobia is an irrational fear, hatred, or prejudice against the Ilsamic religion. These beliefs are a growing problem around the world that has resulted in multiple deadly attacks.

In Christchurch, New Zealand 49 were killed by a white supremacist. Prime Minister of New Zealand Jacinda Ardern described the horror as a terrorist attack and said it was one of the country’s “darkest days.”

Canada is also home to Islamophobic ideology. In February of 2019 the Quebec mass shooter who killed six men at a mosque was sentenced to life in prison with no chance of parole for 40 years.

According to David Schanzer, a Duke professor, terrorism is “politically motivated violence, usually against civilians, to create fear.”

Many people have a notion that terrorist attacks are committed by individuals who live in the Middle East who are attached to terrorist organizations. But terrorist attacks committed by white supremacists with right-wing ideologies are the most prevalent.

Terror attacks have fallen from 17,000 in 2014 to 11,000 in 2017 globally and in the Middle East terror attacks have dropped 40%. However, the United States is facing an increase of attacks by right-wing extremists from 6% in the 2000s to 35% in the 2010s. The U.S. had only six such attacks a decade ago, but 65 in 2017.

Meanwhile, from 2012 to 2015 hate crimes against Muslims in Canada grew 253% and have continued to climb.

A Canadian survey done in 2018 found that most Canadians believe that Islamophobia is increasing at a dangerous rate, but that doesn’t include people who define themselves as conservative. Canada’s Parliament passed a bill named M-103 that condemned Islamophobia trying to combat this problem.

The Islamic Networks Group(ING) speaks out about how the media focuses on terrorism by Muslims even though a recent U.S. survey of law enforcement shows anti-government violent extremists are a much higher threat in North America.

The group believes that there needs to be more than a law to stop the deep-rooted prejudices that are the cause of discrimination. ING says that education about the everyday lives of Muslims and inter-religious engagement decreases Islamophobic responses by more than 50%.

The Hijab

Women who wear hijabs frequently face controversy over their choice to do so. The hijab is a religious symbol of modesty and privacy.

According to Oxford Islamic Studies,

“Since the 1970’s it has emerged as a symbol of Islamic consciousness and the voluntary and active participation of young women in the Islamic movement, a symbol of modesty that reaffirms Islamic identity and morality and rejects Western materialism, commercialism and values.”

Women have been struggling with hateful comments and crimes against them because of their choice to wear hijabs and other religious veils. In Edmonton, a woman and her friends were bombarded with comments from a man at a supermarket, calling their hijabs and niqab “slave scarves”.

That is only one instance where women have had to fight for their right of choice and stand up to the ignorance and racism that they face on a daily basis.

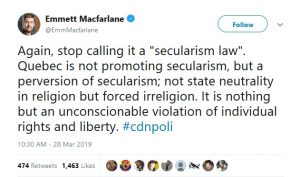

In Quebec, there are political debates over whether to ban the hijab, burka, and other forms of religious veils.

The Coalition Avenir Quebec (CAQ) was elected into power in October of 2018. The party wants minorities to mesh in with the culture. It believe’s banning religious veils separates religion from society, and integrates everyone into the French culture. Debates on the ban of religious garments have been an ongoing discussion in Quebec.

The CAQ is proposing a new law, Bill 21. It would forbid people in authority positions from wearing religious symbols. Symbols include a hijab, kippa, or turban. Authority positions may include Quebec Crown prosecutors, any employees who carry firearms, judges, principals, and teachers. Rob Lurie from CTV tweeted a video about a Muslim woman saying she is not sure what she will do once Bill 21 comes into effect. She feels that the new law is discriminatory and will make her feel unwelcome. Many people responded to Lurie’s tweet by saying that people should have religious rights.

A Montreal teen is fighting the religious-symbols ban in order to pursue his dreams of being a police officer. He has created a group on Facebook called The Quebec Association of Sikhs to oppose Bill 21 because it bans police from wearing a turban. However, the police union in Montreal supports the bill. It is worth noting, though, that only 7.5% of officers on that force are a visible minority.

In the more diverse Toronto police force, religious symbols including turbans and hijabs, have been allowed since 2011 and there are efforts to be more inclusive. If Bill 21 is put in effect in Quebec, Singh says he will still work towards making the Montreal police more diverse.

There are, however, some racialized people that support Bill 21 due to their own experience living in countries where there is religious oppression.

Ameni Ben Ammar moved to Quebec six years ago with her mother. Ammar supports the bill because of her experience in Tunisia. She wants to be able to see a clear difference between religious groups and government. Zahra Boukersi is a teacher who fled religious oppression in Algeria. Boukersi also supports Bill 21 because she feels it is necessary to stop radicalism. When Iran implemented a dress code for women that forced them to wear a hijab, Homan Davoodi left his home country. Davoodi strongly supports Bill 21 and believes that the hijab is repressive.

A global icon of resistance, Shaparak Shajarizadeh has mixed emotions about the Bill. Originally from Iran, she was arrested three times and jailed twice for removing her hijab in public and posting pictures on social media. She fled to Canada from Turkey last year after she was sentenced to 20 years in prison. She feels the hijab is a symbol of sexism but doesn’t believe the government should be able to tell adult women what they can and cannot wear.

Hijab as Fashion Controversy

This ad was posted to advertise a clothing line by “Hoodies.” It assumed that women who wear hijabs aren’t free and represented a negative perspective.

A 2018 Gap ad included pictures of children wearing Gap clothing, one of them a girl wearing a hijab. The model herself was ecstatic about being in the ad wearing her hijab. Many people on social media expressed their approval and had positive comments on the ad. But strangely, people in Canada and France were outraged. Opinions relating to forced child marriage, and other stereotypes such as honour killings were tied to the picture.

Some women have simply chosen not to wear their hijabs to avoid being labeled and having stereotypes thrown at them. Saba Ali, a journalist from the Washington Post, is one of them:

“Without my hijab wrapped around my head and pinned tightly under my chin, I was nothing special. I no longer stood out as the oddity or the outsider. Without that thin piece of fabric, I was just like everyone else waiting in line, blending into the background with my Americano and blueberry muffin.”

Sarah Darsha is currently a host for Rogers television. Being a Muslim woman who wears a hijab she’s faced a lot of racism and prejudice. During a Skype interview, Sarah broke down some misconceptions about hijabs and shared her thoughts on how to eliminate Islamophobia. Due to issues with the quality of the Skype interview, it can’t be posted. However, below, we share excerpts taken from the conversation.

Q: For those who don’t know can you explain what a hijab is and why you wear it?

A: So God has asked, Allah has asked us as women to wear hijab, so we wear it out of obedience to God. Now I love my religion very much. When I wear it [hijab] I actually feel liberated. I don’t feel oppressed at all. I feel like it’s part of my identity. I also feel like when I wear it I’m a walking representation of my religion, which once again I’m proud of. Now hijab shows women that they don’t have to fit into an unrealistic set of beauty. If you walk anywhere and look at any commercial you see that women have to look a certain way–their hair a certain way, their body a certain way–and hijab doesn’t restrict me to that. I can wear a hijab freely, my hair doesn’t have to be a certain way. Hijab isn’t just something over your head. It’s a whole gear, your body is covered.

Q: How would you respond to the perception that wearing hijab is oppressive.

A: That’s not true for most Muslim women. When they wear hijab it is a choice. For me, no man ever told me to wear my hijab. My father never said you have to wear it. My brothers never said you have to wear it. It’s something that they said is completely your choice when you do. It’s a dedication that you are going to make. So you should be ready for it when you decide to do it. But it’s never anything that they forced me to do. I think it’s actually the opposite. After 9/11 when I was still wearing my hijab my dad was worried about me. He was like, ‘I don’t know, do you want to wear it? I’m afraid for you.’ I was like, ‘You know what, no, I’m not afraid. I’ll continue to wear it and I’m happy wearing it. It’s part of who I am.’

Q: Have you experienced discrimination because of wearing a hijab?

A: I definitely have experienced discrimination. You know you get the odd stares here and there and I don’t know, but I think that’s just curiosity. People want to ask you what hijab is. But definitely have experienced discrimination.

Q: How does it make you feel when you personally get these reactions like multiple times?

A: Definitely, it’s uncomfortable. I mean before I had a family I think I had nothing to protect really. I just had myself. I would be more lenient with how I spoke to people if they did come to attack me. But if I do have my kid around me or children and someone’s attacking me, I’m more aggressive. I don’t accept people saying things. I want to show my daughter that you have to show up. That when somebody comes up to you because of your religion, not seeing that you’re a human, then you 100 per cent tell them no that’s not how it is. This is the right way to speak to people. I am human. Just because I have different faith than you doesn’t mean you can disrespect me. That’s how I feel.

Q: If you’re comfortable doing so can you actually share your thoughts on the New Zealand mosque shooting that happened recently.

A: Absolutely. It’s a devastating, devastating act. That’s what I call it. Honestly, ever since it happened I’ve had trouble sleeping because it’s just such a horrible, horrible event… I don’t think anyone deserves to die… I don’t know what is wrong with him. I don’t know how you can do that–how you can kill children, how you can kill women and do that in a place of worship. People come to the mosque every Friday and it’s something that we love to do… It’s our home and it’s equal to someone coming into your home and shooting… I hope nothing like this ever happens again.

Q: I’m really sorry about that. What do you think can be done to deter Islamophobia.

A: I think like I said you just talk to a Muslim. Honestly just go up to a Muslim and talk to them… you will see that we’re human just like anyone else. The key to avoiding Islamophobia, the key to avoiding racism, is to humanize people, not to dehumanize them.

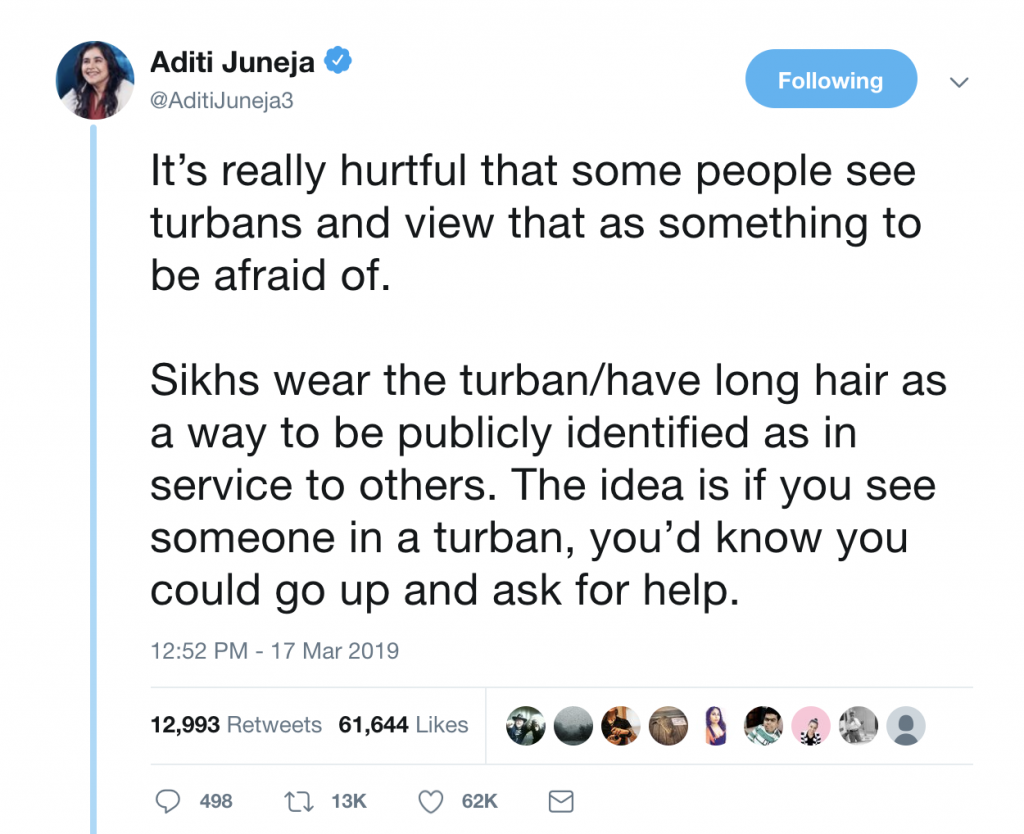

Turbans

Turbans are also worn by choice. Sikh men wear turbans as a sign of respect to God and representation of their faith. As they do not cut their hair, the turban keeps it in place, and clean from any dirt and dust.

Sikh men have been attacked, threatened and had racist comments spewed at them. For example, in 2018, a man in Ottawa was threatened with a weapon, attacked with racial slurs, and had his turban torn off his head and stolen from him along with his phone.

But things are changing. Baltej Singh Dhillon became the first RCMP officer allowed to wear his turban as a part of his uniform. He became the voice and face for Sikh men in the RCMP:

“I feel I am no longer judged by what I wear on my head, but rather my performance as a police officer.”

The information campaign #AskCanadianSikhs started after a man waiting in a line at a Habs game was asked if he was Sikh. After saying he was, he was then asked if there if there was a relation between Sikhs and terrorism. The question was not meant to be mean or disrespectful, but it took the Sikh man by surprise. The Twitter campaign was seen as an opportunity to tell stories and educate the public on a wider platform.

Rupinder Singh is the founder of American Turban and uses humour to share knowledge:

“Sikhism is a religion of about 25 million people around the world. It’s the fifth largest world religion by population. Most of the religion’s followers are in India, but there are about 500,000 Sikhs in the United States. That’s a lot of turbans!”

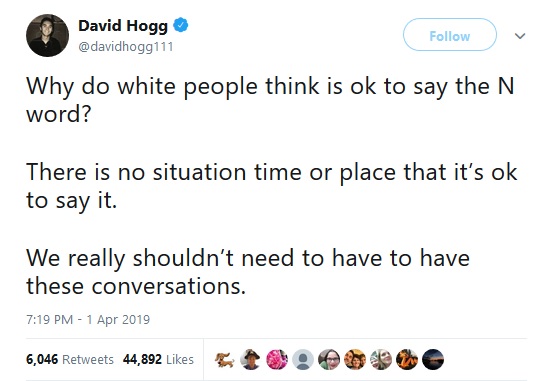

The N-word

Perhaps there is no word more loaded with controversy than the N-word. This is not a six letter word that everyone can use freely. It represents many people’s experiences of oppression and discrimination because it was a word created to dehumanize Black people. This six-letter word holds thousands of painful experiences, but yet people still think it’s okay to use it today. Why? That’s what we’ll explore in this section as we break down what the N-word means and why it’s offensive. In the clip below YouTuber/Podcaster Marlon Palmer talks about the difference in the “a” and “er” endings of the N-word. After the clip, we’ll share the history of the N-word in a visual timeline.

As noted in the above timeline, the use of the N-word in school material can be difficult for Black students. Tristan Miller is a student in high school, who shared his experience about being the only Black kid in class when a movie was played that repeatedly used racial slurs. In the clip below he describes it as a “shocking” moment. After Tristan’s clip, we’ll take a look at how a hoodie can insight prejudice.

Hoodies

The idea of youth perceived as threatening because of wearing a hoodie came to the forefront by the death of Trayvon Martin. Martin was a 17-year-old boy who went to a convenience store to buy a pack of Skittles. While walking home he crossed paths with George Zimmerman. Zimmerman claimed to be threatened by Martin and shot him. Martin was wearing a “dark hoodie” at the time.

Hoodies became popular in the 80s when breakdancers and graffiti artists began wearing them, turning them into clothing for the sake of style versus performance. Hollywood has amplified the idea of hoodies being threatening, with people wearing hoodies in movies and music videos often portrayed as gangsters or “dangerous thugs”–those who wear a hoodie are “bad.”

The New York Times chronicled the ‘Politics of Hoodies’:

“On the street, a black guy in a hoodie is just another of the many millions of men and boys dressed in the practical gear of an easygoing era. Or he should be. This is less an analysis than a wish. The electric charge of the isolated image — which provokes a flinch away from thought, a desire to evade the issue by moving on to check the sizing guide — attests to a consciousness of the hoodie’s recent history of peculiar reception.”

In the next section we’ll examine how racism is embedded in a variety of institutions, like the health and justice systems, or Systemic Racism.